"The experience of true insight is the simultaneous awareness of both stillness and active thoughts. According to the Maha Ati teaching, meditation consists of seeing whatever arises in the mind and simply remaining in the state of nowness. Continuing in this state after meditation is known as "the post-meditation experience."

Jigme Lingpa, translated by Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche

"Do not resolve the Dharma,

Resolve your mind.

To resolve your mind is to know the one which frees all.

Not to resolve your mind is to know all but lack the one"

Guru Rinpoche

Dzogchen training is based on the recognition of natural awareness which is referred to as ordinary mind. Natural awareness is the true nature of our mind when it is free from habitual reference points. This is the quality of our present experience which is uncontrived, undistracted, nondual awareness. It has been described as naked and unborn in the sense that it is awareness which is stripped bare of any karmic conditioning or habituation. Ordinarily in our day to day lives our minds are continually involved in habitual thought and projection. This habitual mode of being is generally how we operate and what keeps us trapped in a cycle of ignorance, delusion and suffering. Habitual thought, projection and the compulsive fixation on what arises in our minds obscures our recognition of natural awareness. Therefore we can understand dzogchen training as a method which purifies the mind of habitual, karmic conditioning allowing us to recognize ordinary mind. In this sense, natural awareness is beyond the reference points of habitual mind. This is what Trungpa Rinpoche referred to as Crazy Wisdom in his early seminars in the west.

"Once again if you don't meditate you won't gain certainty. If you do meditate certainty will be attained. What kind of certainty should be attained? By meditating with strong diligence, the uptight fixation on solid duality will gradually grow more relaxed. Your constant ups and downs, hopes and fears, efforts and struggles will gradually diminish as a natural sign of having become fully acquainted. Devotion to your guru will grow stronger and you will feel confidence in his oral instruction from the very core of your heart. At some point, the conceptual mind which solidly fixates on duality will naturally vanish. After that, gold and stone are equal, good and evil are equal, food and shit are equal, buddha realms and hell realms are equal--you will find it impossible to choose."

Dudjom Rinpoche

Since habitual mind depends on constant movement, distraction and the manipulation of what arises in our experience, the fundamental form of practice in dzogchen is to sit still and be undistracted -- to leave whatever arises in our mind as it is -- that is, not to manipulate or strategize our thoughts or the sights, sounds and sensations that we perceive. This is called the "resting meditation of a kusulu."

"Keep your body straight, refrain from talking, open your mouth slightly, and let the breath flow naturally. Don't pursue the past and don't invite the future. Simply rest naturally in the naked ordinary mind of the immediate present without trying to correct it or replace it. If you rest like that, your mind-essence will be clear and expansive, vivid and naked,without any concerns about thought or recollection, joy or pain. That is awareness (Rigpa)."

Khenpo Gangshar

The basic instruction for kusulu meditation according to our lineage is first to sit in the posture of the Buddha. This is the seven-fold posture of Vairocana. Essentially the legs are crossed and the spine is straight. Having taken that posture one then should "leave the body like a corpse in the charnal ground." This means to not have hope and fear about the body. In terms of the speech, one leaves the breath as though it were a broken instrument -- a lute whose strings have been cut. Again this is referring to not having hope and fear about the voice or breath. It is left as it is.

With the mind, the instruction is to leave the mind as it is -- without hope and fear. And whatever thoughts arise in the mind should also be left without engaging by either accepting or rejecting them.

"Whatever arises as objects in awareness

--Regardless of what thoughts arise from the five emotional poisons ~

Do not allow your mind to anticipate, follow after, or indulge in them.

By allowing this movement to rest in its own ground, you are free in Dharmakaya."

Guru Rinpoche

Distinguishing between Sems and Rigpa

"Mind (sems) is like the clouds assembled in the sky. Therefore you must gain stability in awareness (rigpa) which is like a cloudless sky. You must be able to purify the aspect that is like the clouds in the sky. Through this you will be able to separate mind and awareness."

Khenpo Gangshar

This particular method of practice depends on being able to separate or distinguish between confusion and realization. This means being able to tell the difference between being lost in a daydream --or just zoned out --and being present-- i.e. not following thoughts or repressing them. "Sems" in Tibetan refers to what in Buddhism has been translated into english as ego. It is not a good translation in my opinion because of all the baggage connected with the word in the english language. In this case, ego as 'sems' is just the tendency to habitually fixate on mental projections which arise in the mind. This creates a fictional dream world called samsara that sentient beings tend to think of as real and habitually attempt to solidify. It is a fundamental confusion. "Rigpa" is the Tibetan word that refers to awareness beyond habitual reference point-- beyond 'sems' or after sems has fallen apart -- which it does naturally moment to moment. Rigpa is what Trungpa Rinpoche refers to as "basic sanity."

"Place your body in the sevenfold posture of Vairochana. Let the nonarising nature of your mind-- this empty and luminous awareness, this primordially pure and spontaneously present essence- remain in the state of the fourfold resting of body, speech and mind.

Don't pursue what has passed before, Don't invite what hasn't occurred, and don't construct present cognizance.

The fourfold resting is:

Rest your body like a corpse in a charnel ground, without preference or fixed arrangement.

Rest your voice like a broken waterwheel, in a state of stillness.

Rest your eyes like a statue in a shrine room, without blinking, in a continuous, focused gaze.

Rest your mind like a sea free from waves, quietly in the unfabricated and spontaneously present state of the empty and luminous nature of awareness. Let your mind rest, totally free from thought.

The earth outside, the stones, mountains, rocks, plants, trees, and forests do not truly exist. The body inside does not truly exist. This empty and luminous mind-nature also does not truly exist. Although it does not truly exist, it cognizes everything. Thus to rest in the state of empty and luminous awareness is known as the ground of cutting through."

Vajrayogini

trans. Eric Pema Kunsang

In order to distinguish between sems and rigpa the kusulu works with body, speech and mind in a particular way. "Leaving the body like a corpse in a charnal ground" means that we don't engage with the physical sensation of our body in an habitual way. When we relate to the body in this way we are simply present with those sensations and they root us in an experience beyond our habitual daydream or psychosomatic experience of the body. Its not that our experience of the body disappears in meditation, but we relate to it without manipulation based on habitual mind. This is the nirmanakaya.

This is the same with our breath, which in this context is regarded as "speech." The breath is left alone without manipulation but is still a baseline experience. We are breathing and that brings us back to a direct experience of being present without complication. Utilizing our direct experience of body and speech in this way is essentially the method of meditation for a kusulu practitioner. This is the sambhogakaya.

There are some techniques that Trungpa Rinpoche gave his students regarding the use of accentuating awareness of the outbreath which are very helpful for distinguishing between being caught in an habitual daydream and being present. These techniques should not be regarded as some type of saving grace. In other words, with the technique Trungpa Rinpoche instructed his students to use, we utilize the outbreath as a neutral reference point. Being aware of the outbreath is just momentarily realizing you are here. Having a technique is just a reminder. If you are daydreaming on the meditation cushion at some point there will be a gap in your daydream and at that moment you remember that you should go back to the outbreath. There may be some sense in that moment that you weren't "here" in the previous moment. That is the technique. There is no effort to push "thinking" away to dwell in stillness or to use the concentration on the breath to induce a kind of trance-like state. None at all. You are "here" with the outbreath, then let it go. You are "here;" then, let it go. By sitting still and allowing the breath to be as it is , we wake up in the midst of our daydream-- moment to moment.

Sems is recognized as engaging in any thought of the past; any ideas of what might happen in the future and any conceptual reckoning in the present. Sems is engaging in any of these thoughts -- habitually or compulsively. In the abhidharma we study the five skandhas -- form, feeling, perception, formation and consciousness. This is all sems. But to understand how we experience sems is that a random thought bubbles up in our mind and we react to it. Whether it is a memory, a future projection or reckoning in the present-- when we react habitually we think of that thought as happening outside of our minds. That is the definition of duality. That is the first skandha. Form. Once we do that -- and we do that based on coemergent ignorance-- then we are on a little trip in our minds. You can call this trip the nidana chain or just samsara. You can call it a daydream -- because that is what it is. It is also the basis of our habitual conditioning: i.e. of karma.

We are used to the idea that spirituality is going to give us some pleasurable answer-- some ice-cream. Lots of meditation traditions including yoga and qigong promise better health, longer life, etc. We expect that from our religions and therapies. We expect that from our little mindfulness practice. We expect them to provide some comforting security blanket. We want to be psychologically comforted.

Dzogchen doesn't promise any of these things. It doesn't promise any security for habitual mind. It is about showing you reality beyond your habitual reference point directly. Dzogchen meditation, if we can even say such a thing, is really about getting bored with sems to the point where one wears out dualistic confusion. Trungpa calls it complete hopelessness, in "Crazy Wisdom." When we present these teachings it is easy to stress all the good aspects but so easy to misunderstand the main point. If we aren't careful we become salespeople trying to convince everyone that Dzogchen or Buddhism or Shambhala is the best kind of product. It will save the planet. It will right all wrongs. It will answer all of your questions. Who is kidding whom?

In general, people are not that interested. They haven't understood the shortcomings of habitual mind. It is difficult to understand any of the Dzogchen or mahamudra teachings because we haven't really seen how our own minds actually work-- or don't work. When we first sit on a meditation cushion with no entertainment it is very difficult to actually understand what is happening. That is why practice and study go together. Once we begin to look directly at our minds in this way we can begin to hear the teachings properly.

People mainly want to make samsara better, or more entertaining-- so that they can avoid their minds altogether. Even "Dzogchen" and "Shambhala" become methods of entertainment and distraction or the reason to have social gatherings-- so that we can avoid embarrassing moments where things don't go smoothly-- like at the moment of death, for instance.

Luckily nowadays with our constant addiction to handheld devices we can keep the entertainment going indefinitely-- or as long as our battery is charged or we have cell reception. But this lineage is not talking about being healthier, about eating right, having healthy relationships or even about conventional notions of sanity. We are "crazy" like that. We are not talking about keeping our samsaric mind entertained and "pingpong balling" past the gap. This path has nothing to do with the eight worldly dharmas. And the practice of meditation itself in this tradition is boring. It is lonely. It is looking at your crazy mind as it is with no buffer. No entertainment. No promise of anything greater. The true motivation for this path is understanding that we will certainly die; we just don't know when-- and we can't take our cell phones into the bardo. There is no cell reception in the bardo.

"Sincerely take to heart the fact that the time of death lies uncertain. Then, knowing that there is no time to waste, diligently apply yourself to spiritual practice." Tsele Natsok Rangdrol

The Bardo of this Life and "Precious Human Birth"

"Bardo" simply means the experience between two points. There is an origination point-- for our lives that is the moment of our birth. We do not remember being born. The other situation is our death. We do not know when we will die. In the meantime we have the relative stability of a human body and an environment that supports the causes for continued life. These circumstances are as fragile as a bubble floating on the surface of the water. We are one breath away from death at every moment. When we sleep we have dreams-- these dreams generally are simply habitual mind blowing every which way because we have momentarily lost the stabilizing factor of the body. "To sleep perchance to dream."

The experience of the dream gives us a glimpse of how little control we have of our karmic habitual mind. We can have horrible dreams or pleasant ones -- and when we are dreaming we generally don't realize we are asleep and so we suffer the pleasures and pains of the dream as though they were really happening.

There are stories

Of where the dead

Go

But I don’t know

Anything

About that

Sometimes

I think

You have just

Moved

To another town

That if I knew

The address

I could drive there

In my car

And sometimes

I see you in

My dreams

Telling me

You are

Real

Before

I wake up.

At this moment, we have woken up momentarily in a precious human birth and we have an opportunity to realize mind beyond habitual, dualistic reference point. It is an opportunity most of us waste. Its like we have one day before we go back to endless suffering. We are deposited on an island of gold-- gold being the realization of wakefulness. On that island are numerous distracting pleasures-- video games, relationships, earning a living that makes us proud, raising a family, our cute dog...what we think is happening in the world. In the midst of this dream we hear the Dharma like a bell ringing in the distance. We think we have lots of time to explore that after we take care of these other important things.

We don't have time.

We need to go towards the Dharma. We should drop everything. In this dream we have one day, actually... The moment that day is over will feel the same as this moment right now. Have we utilized this precious human birth? Will we return empty-handed from this island of gold?

The meaning of this life that we now have is that we have heard these teachings on how to wake up from our daydream. This is our "precious" opportunity.

The "reality" we are talking about here is not some imaginary mystical experience of "transcending duality" or "becoming one" with...whatever-- which is based on some pleasant "spiritual" daydream. We are simply talking about the basic sanity of being able to tell when we are daydreaming and when we are not. On the basis of recognizing the difference between these two things in our direct experience, the whole path of authentic practice becomes possible. If we don't understand this at the beginning of our journey then we end up chasing a fantasy of spiritual experience which leads to further delusion.

The much sought after "pointing out" that so many western students chase after is nothing other than this-- being shown a mind that is not lost in daydreams. It is supposed to be helpful for a student on their path as a practitioner to receive the "pointing out." Unfortunately, unless a student is able to utilize such a blessing in the way I have talked about here-- it can become an obstacle and hindrance to any genuine realization. In particular, having received the "pointing out" is not the end of the journey at all. It is only the hint of a beginning. One analogy the Tibetan teachers use is that it is like being shown the road to Lhasa. It is up to us to walk there.

Without intensive practice before, we will lack the psychological sophistication to understand what is being pointed out. Without practice after receiving the pointing out we never reach our "destination."

In general there seems to be many misconceptions about what a guru is for in the Buddhist tantric tradition. The tibetan word is Lama --"guru" is a term which carries quite a lot of baggage from the hindu tradition, therefore I prefer to use the term "Lama." "Lama" means "someone who carries the burden". Ultimately the lama is the Vajra Master who knows the nature of mind as nonreference point experience and is driven to wake us up. When you have a relationship with a person like this-- every engagement with them carries the possibility of meeting the mind of nonreference point experience. This transmission depends on the devotion of the student. The nature of mind is simply experience or awareness beyond habitual reference point. It is an open secret.

This transmission can occur in many ways-- very elaborate ways or very direct and simple ways depending on the Lama and the prospective student's capacities and how the situation develops. Generally, this transmission depends on the mandala set-up and the "guru principle." The student needs to be entered into a training situation or "practice container" in order to develop the ability to receive the particular magic we are talking about here. It is important to realize this transmission doesn't happen in a vacuum or in a Hollywood movie in the way we imagine with our habitual preoccupations and fantasies. The experience of mind beyond habitual reference point is the dharmakaya.

There is a story in "Blazing Splendor" where a naughty young tulku recieves the "pointing out" from an old monk who admonishes him to "not wander." Throughout his life he would remember this grouchy, old monk from his childhood as one of his root lamas --the one who first showed him the nature of mind. After his 12 trials with his root lama, Naropa recieved this transmission from Tilopa when Tilopa slapped him in the face with his sandle.

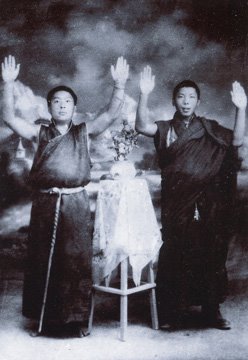

Throughout our lives we may have many lamas. Trungpa Rinpoche had 17. We usually have one who makes a very strong impression and this person we think of as our root lama. Trungpa Rinpoche's root lama was Jamgon Kongtrul of Shechen. He also had a very strong connection with Khenpo Gangshar Wangpo-- a close disciple of Jamgon Kongtrul.

Co-emergent Wisdom and Self-Liberation

"I would recommend that you don't worry about future security, but just do it, directly and simply." Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

"Second, for identifying vipashyana, no matter what thought or disturbing emotion arises, do not try to cast it away and do not be governed by it; instead, leave whatever is experienced without fabrication. When you recognize it the very moment it arises, it itself dawns as emptiness that is basic purity without abandonment."

Padma Karpo

The moment when we realize we have been following a thought is actually the moment of co-emergent wisdom.

"At the moment of seeing, the thought has dissolved, it has vanished, and you have arrived at the completion stage."

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche

If we understand the projection and fixation on what arises in the mind as sems then we can understand that every time an habitual reference point falls apart, which it always does, there is the possibility of recognizing awareness beyond ,or as the background to, the habitual involvement with "thinking". From our samsaric perspective this experience is called "impermanence," and is considered the cause of our basic anxiety; but from the tantric point of view it allows the possibility of co-emergent wisdom. Trungpa Rinpoche called this "the great switcheroo."

Co-emergent wisdom or "the wisdom born within" is resolved through practicing in this way. This is why clinging to a fabricated meditation state which is peaceful, clear and comforting is missing the main point of practice entirely. It may make you feel calmer and help you fall asleep at night but it will not lead to enlightenment.

There is an instantaneous flip of perspective that happens the moment you recognize that you are "thinking" --i.e. habitually engaging in thoughts. That moment is awareness that is free from habitual reference point-- Rinpoche called it the "gap". That is the meaning of the saying "the more thoughts, the more Dharmakaya." This method of shamatha-vipashyana practice is said to be spelled out in Gampopa's commentary on the Samadhiraja Sutra. I have not been able to find that commentary but I will take the Vidyadhara's word for it.

Trungpa Rinpoche explains that by disowning any attempt to maintain a concentration on the breath after the outbreath we allow a moment of weakness in the technique. This allows us to see whatever thoughts are bubbling up in our minds without trying to repress thinking through concentrating on a technique.

The point of the practice is to see our minds clearly-- to see everything that is arising in our minds clearly without trying to suppress or follow what arises. And because we are simply sitting in a room where nothing is happening doing nothing we can recognize what arises without leading or following the thought. This is how we "purify" sems-- by exposing it to our present awareness.

"When it happens that you do get involved in thoughts that recollect the past or entertain the future, then let be directly in awareness. If a thought pattern continues, there is no need for a separate antidote since whatever takes place is liberated by itself. What occurs spontaneously is the radiance of your own mind. To see it with vivid clarity is the essential instruction."

Tsele Natsok Rangdrol

There are three fundamental ways of relating to what arises in our mind during meditation practice: Thinking, not thinking and nonthinking. "Thinking" in this case means engaging in thoughts habitually and compulsively. Something pops up in our mind and we react out of coemergent ignorance. A memory of our old girlfriend pops up and we react as though she were actually standing right in front of us. That is a delusion. Our old girlfriend isn't there. We are daydreaming constantly. Doomscrolling in our discursive mind. As soon as that thought dissolves we jump to the next thought-- generally it is a continuation of some storyline-- we like our old girlfriend or we don't. On and on the discursive thinking goes-- though there are gaps between these stories or thoughts we just speed over them-- because habitual mind is terrified of the gap. All the energy of habitual mind is put into the attempt to cover any gap in projection and fixation.-- which , by the way, always fails. That is why sitting in a room where nothing is happening doing nothing--i.e.: "nondoing" --is so difficult from habitual mind's point of view. It is why it is so effective from the point of view of wakefulness.

" Not thinking" is either hanging out in a blank state which has no thoughts but is like an ignorant sleep or it could also be the result of repressing all thoughts through the development of a trance-like state. We are so focused on our meditation technique that all thinking is interrupted and we maintain an intensive concentration which actually represses the arising, dwelling and cessation of thought. It is a very ambitious approach. We perch on our seat waiting for the experience of enlightenment. It is yet another method of habitual mind to avoid the gap. The problem with this is that we are not actually addressing the root cause. When we stop meditating and a thought of our old girlfriend arises we will be carried away by an habitual reaction to that thought. This is the view of the Huashang Mahayana, the Tirthikas and the "cessation of the Shravakas," and the view of the modern "mindfulness movement." It is an aberrant path because it is based on a type of attachment to the comfortable peace of nothing arising in the mind-- which is a pleasant kind of meditation experience. One can even have some special powers which arise from this state-- bliss, clarity and cessation; clairvoyance, etc. which only reinforces one's pride and attachment to one's skill in meditation.

"Nonthinking" is a completely different thing and it is the essence of Mahamudra and Dzogchen. It means we are not deluded by what arises in the mind. The first moment of arising where coemergent ignorance usually engages in a dualistic interpretation is seen through with rigpa-- "first thought." Then whatever arises "is seen to be transparent and unreal." Everything that arises as experience has the "one taste" of nonthought. So a thought arises but " it has no legs and no tentacles" according to "The Book of Sue." What does that feel like? It is like you have been away from home for a while and when you come back it feels familiar but weird. Generally we call it "groundless and rootless." You could also call it Padmasambhava's charnal ground or "meeting the mind of the guru. " "Meeting Vajrayogini face to face" is another way to describe it. This is "Sacred World."

Trungpa Rinpoche calls this "The Blue Pancake" in "Journey Without Goal."

From the point of view of habitual, dualistic fixation it is like hell. Space seems solid and threatening. I felt this when I was around the Vidyadhara or the Vajra Regent.

It might feel like your vacation in a foreign land has gone on too long and now you just want to get back to your cozy home because you are so irritated with your hubby, or room service-- but you can't seem to get back. You can't not see "the blue pancake." You can't run to your neighbor and yell, "Help, the blue pancake has fallen on me." He will be the blue pancake as well. All the usual habitual reference points don't create a feeling of solidity and security at all. They never did but now it's inescapable. There is no security. No habitual comfort.

Conceptually we usually try to resolve this with eternalistic or nihililistic views-- or binge watching Netflix, but we can't erase the direct perception which is inescapable.

Your mother, your father, your wife, husband-- even your childhood home appears strange and unfamiliar around the edges.

Blue pancake.

You might be going crazy-- it's hard to tell and there is no one to talk to except your root guru-- who is the ultimate blue pancake.

It can be felt as "panic." It usually is. In fact, Trungpa Rinpoche once said that all his tantra students should be in a state of panic.

"Generally, logical answers provide security. Logical conclusions bring us some comfort. Our logic tells us that if we do this, then that is going to happen. It creates a seemingly predictable world. One tends to plan everything out, program oneself altogether. One has to learn not to indulge in that particular comfort of overlapping answers. It requires bravery to stop doing this kind of obsessive logical analysis and abandon the chain reaction of answers. It requires the bravery that is willing not to involve itself with that comfort. One must stop fantasizing for one's security and come to the point of no-mind, or nonlogical thinking. The only way to turn off that process of logical thinking is just to step out of it. When there is no logic, we begin to see things very clearly, but we also begin to feel cold. That area, which is free from habitual mind, may feel very bleak and cold because it seems so unfamiliar. So when we experience it, we usually try to reestablish our familiar territory further and further. In order to liberate yourself from habitual patterns, whenever you feel any kind of cold and bleak mysterious corner, instead of trying to fill that mysterious area with anything else, you should just step into that cold and bleak area-- because it is not participating in the logical process of ego. That's all you can do. In a way, what you do is to just not do anything. Whenever there's a mysterious dark and bleak corner where there could be mental spiders or mosquitoes or bats, we tend to manufacture some logic, some kind of alternative to explain away those scary things in the dark. There could be anything in that space. Instead of investigating these terrible things, we would like to make everything homey and cozy. We try to reassure ourselves that everything will be okay. We're always trying to avoid those dark areas. When you feel this fear of the void, that's exactly when you need to leap. Just go into that space. I don't think you'll be afraid while you're leaping. You're afraid beforehand. The leap itself transcends fear. It is rather like a parachute, isn't it? You are terrified by the thought of parachuting, but once you are in the air, you are ready. The fear dissolves, and the open space of no-mind opens up." Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

This is called mahasukkha. Great bliss. It is also "luminosity-emptiness." As practitioners we are just getting more familiar with this non reference point experience. The instruction is to "lean in."

The Big No

Modern theoretical, psychological therapies are based on the notion of healing past traumas that patients hold in their mind and body. The idea is that these traumatic experiences are conditioning one's present experience and creating a state of anxiety in the patient that prevents them from living a fulfilling life. A current event can "trigger" a past traumatic experience that we live again as though it were really happening. This is what is called "post traumatic stress syndrome." All of this sounds very similar to what I am talking about as "sems" in Dzogchen training, but the idea of how this trauma is healed and what a "fulfilling life" is in psychotherapy lacks the "view" of Dzogchen. It is more concerned with the idea of psychologically comforting the patient. Therapies consist of taking certain drugs or talk therapy-- Jung and Freud were into dream analysis. There are many theories and practices to address problematic behavior, stress and anxiety. The ideas of "healing" in psychotherapy and psychology ,in general , are based on projections of habitual, dualistic mind. They are not true paths to the realization of the nature of mind.

" In actuality, the non-Buddhist schools, whatever they may say about presentations of the two truths and so forth, are formulated based upon clinging to things and therefore do not have a proper path to liberation." Khenpo Gangshar.

There are now schools of psychology -- "Transpersonal Psychology" and "Contemplative Psychotherapy"-- which essentially attempt to co-opt the practice and view of authentic dharma.

"Somebody has to say this therapy thing is bullshit. Let's stop this. Let's have more respect for people's minds altogether than say, "Well come back and see me next week." You know. About what? I'm not trying to be funny. I actually mean this. As much as I can. The notion of trying to work with somebody's mind is bogus. There is no such thing to begin with. What are you working with? Your own projection. When we started the maitri program years ago Rinpoche said, "The curious thing that happens is that when a crazy person comes into the room you become crazy on the spot." To understand that, if you are a therapist, then you understand everything and you can stop that nonsense of thinking you are helping somebody. Help is much bigger than that. Much vaster than that. You have to become like the elements. You have to become like the crazy person which means like wind, like fire, like rain. Like all the elements. Otherwise you can't communicate to people's minds... The whole idea is fucked from the beginning! It is! You know, if you study the Dharma and Lord Gampopa talks about the different kinds of free and well-favored births. Right? And everybody I take has studied that. And there are the ten and eight conditions for a free and well-favored birth. And when you study those things and you see people who do not have those conditions then you understand why they cannot understand the Dharma. They can't understand the plain reality, just things as they are. And you don't try to give them psychological concepts or helping aids to make them feel better about the fact that they can't get it. You have to understand cause and effect and free and well-favored birth. And when you understand that its possible we can talk about "mental health." Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin

From the Dzogchen view, practice and conduct -- this type of therapy is not the point at all. The experience of wakefulness has nothing to do with calming past trauma in this way.

Klesha activity is always directed towards some kind of resolution which is based on dualistic fixation. Dzogchen isn't about that kind of resolution. With klesha you want to act on the object. You want to release the energy of the klesha. With aggression we want to kill or harm the object; with passion we want to possess or fuck the object; ignorance is just falling asleep and not realizing that we are dreaming. What we discover through practice is how to rest in the texture of the klesha without releasing the energy in its formulaic direction. This is resting "without leading or following." The energy of the klesha wakes us up rather than energizing our daydream or our "PTSD" experience. Actually, sometimes it's hard to tell which is happening. We don't resolve kleshas in terms of a dualistic narrative. Kleshas are resolved through the recognition of natural awareness-- non reference point experience --which is inherent in the experience of the texture of the klesha.

The higher Tantras are considered "transgressive disciplines" because we are eating the kleshas in this way. In the lower yanas kleshas are considered poison because they are the energy that churns habitual mind--sems. In the higher tantras the tantric yidams like Vajrayogini or Chakrasamvara are manifestations of vajra klesha-- the aspect of klesha which wakes us up-- vajra passion, vajra aggression, vajra ignorance. This is because kleshas are more powerful than sems attempt to create an habitual reference point. That is why our experience of klesha is so painful from the samsaric point of view. Habitual mind just spins faster and faster trying to manipulate the energy of klesha with hope and fear which it cannot achieve. This is perfect for recognizing mind beyond habitual reference point--rigpa.

The transgressive tantras like Vajrayogini are called "the left-hand" tantras. This comes from the brahmanical tradition in India where the left hand was considered impure and the right hand was considered pure. You eat with your right-hand. You wipe your ass after you poop with your left-hand. In India if you were a Brahmin it would be a shocking taboo to eat with your left-hand. Culturally, everyone knew this and people would freak out. You can feel that edge when you practice the Vajrayogini Sadhana even though we don't live in a brahmanical culture. You could feel that edge around the Vidyadhara Trungpa Rinpoche and the Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin. Maybe you can feel that edge as I talk about it now. It's an interesting twist that undermines habitual reference point. That is why Vajrayogini practitioners bless everything with their left-hand and why during feast the samaya substances that we eat always include meat, alcohol and torma. They symbolize the three root kleshas.

From the perspective of the left-handed tantrika, the answer of how to wake up is right in the middle of our klesha attack. It is a profound method for recognizing experience as non reference point. It is absolutely necessary to understand these higher tantric practices from the view of dzogpachenpo. It is important to realize that the practice of deity yoga is a profound method for infiltrating marigpa --coemergent ignorance-- with rigpa. Otherwise, we can really get confused-- or, worse-- not understand or honor the profundity of these practices.

A lot of people think they will just skip the tantric practices and just do Dzogchen. So they sit in a room doing nothing-- thinking they are doing Dzogchen. They are not aware of the subtle or not so subtle subconscious conditioning in their minds.

The path of deity, mantra and dharmakaya is the profound method for recognizing jinlap which is "meeting the mind" of the guru. Without the recognition of jinlap it is simply impossible to realize the nature of mind-- call it Dzogchen or Mahamudra. It is the same mind-- Tilopa's mind; Padmasambhava's mind. For beginning students in Trungpa Rinpoche's lineage we get it right off the bat when we do the Sadhana of Mahamudra on the full and new moon. That feeling is not just caused by hyperventilation while you say the triple hum to yourself. That is jinlap. The blessings of the combined practice lineages of Padmasambhavavand Karma Pakshi.

Feedbacks and No Feedbacks

In Tantric practice we eat this energy in order to disrupt habitual mind and thus recognize non referential awareness as coemergent wisdom. This is what we mean by "looting" and "ransacking" the privacy of the kleshas. This is how we cut the root. What arises as experience from this method is recognized as the mind of the guru, lineage, deity. Subject, object and activity are completely infused with the "one taste" (rochig) of non reference point awareness. This is jinlap, "sacred world." This is best done in the presence of your vajra sangha. They are there to witness your freak out. Sometimes you are there to freak them out. Welcome to "Sacred World."

When a genuine yogi is tuned in to the situation they manifest in ways which are not fabricated from the point of view of habitual mind. This is a manifestation of crazy wisdom. Generally there will be some feedback from the phenomenal world, In fact, that is always the spark. The engagement with this situation takes bravery and yet the yogi may not feel ready to extend himself like this. This is not about comfort. His actions are usually interpreted from a samsaric perspective. This is a situation that Trungpa refers to as both "Feedbacks" and "no feedbacks."

There is a provocative aspect which can lead to lots of consequences from the point of view of conventional reality. This "practice" is like throwing oneself off a cliff. Naropa was exploring this through his 12 trials with Tilopa and Trungpa Rinpoche and the Vajra Regent were constantly operating in this way.

The result for an authentic yogi is waking up when you hit the ground and then experiencing the aftermath. There is a natural speed limit for a yogi -- but generally, the inspiration of devotion pushes everyone outside of their comfort zone. From the worldly point of view this looks suicidal. The inspiration to act arises out of non reference point. The result is non reference point experience.

When the energy of the klesha is co-opted by habitual mind that is "crazy crazy"--the four maras. When the energy of the klesha is "self-liberated" to disrupt habitual reference point and recognize non reference point experience-- that is "Crazy Wisdom"-- the four karmas. Engagement with the phenomenal world is the method. You will only know for sure in the moment which situation is occuring because you recognize non reference point experience and go towards it. Again, this is what happens as a yogi dies too. Same thing. As a yogi lives a yogi will die. This is what practice / life is in every moment.

The energy of lust ravishes away habitual reference point; the energy of anger rages away habitual reference point; and, the energy of ignorance stupifies and paralyzes habitual reference point. These are the textures of the root kleshas as non referential awareness --Their "vajra quality."

There is no security in lust

Except

In where you

End up

Which is counter intuitive

The Vajra Dharma is counter

Intuitive

You would like

A home

And you think you

Know what home is

In Dharma

When you

Lose your home

You discover

Your true home.

It is like

Everything

Else

The security

Is recognizing

Where you are

Recognizing

Where you

Have always

Been

And when you wake up again

After your trip

Recognizing

That this place is the guru.

In our lineage

We work

With lust

First

Anger is

A little more dangerous

But

Make no mistake

It’s all dangerous

From our

Habitual

Attempt

To solidify this and that

It’s not reasonable

Don’t make that

Error

Or intellectualization.

Be raw

Emotionally

And cynical

About any attempt

To justfify

Or denigrate.

Anything and everything

At all.

From the point of view of modern psychology and psychotherapy, non reference point experience would certainly be considered a form of mental illness. It is not an experience which is comfortable for the mind of habitual reference point.

What would have happened if Milarepa was able to visit a graduate of the Naropa Institute's Contemplative Psycho-therapy program and resolve all of his family trauma with his Aunt and Uncle? Do you think he would have realized Mahamudra?

"The simultaneous experience of confusion and sanity, or being asleep and awake, is the realization of coemergent wisdom. Any occurrence in one's state of mind-- any thought, feeling or emotion-- is both black and white, it is both a statement of confusion and a message of enlightened mind. Confusion is seen so clearly that this clarity itself is sacred outlook." Chogyam Trungpa

A few years ago I remember watching a PBS special on the Buddha. It was actually called "The Buddha." They relied on American Academics--professors and psychologists --to explain the Buddha's teachings. They were considered "the experts." I think there were a couple of American Vipassana teachers. There were no Dzogchen or Mahamudra masters. There were no Tibetan masters. There was no mention of non reference point experience. In the west the Buddha's teachings have been absorbed and co-opted by the Western conceptual view.

"I think that is a misunderstanding. In terms of feeling that certain ways of doing things might help you, there is still a sense of therapeutic practice. Meditation is not a therapeutic practice at all. We seem to have a problem in this country with the sense that meditation is included with psychotherapy of physiotherapy or whatever. A lot of Buddhists feel proud because meditation is accepted as part of the therapeutic system, a landmark of the Western world. But I think that pride is simpleminded pride. Buddhism should transcend the therapeutic practice of meditation. Relating with gurus is quite different from going to your psychiatrist.

Student: But out of that experience I'm afraid of falling into the trap of getting too involved in the therapeutic aspect, because it does in fact dissolve pain. I mean that is the experience I have.

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche: You shouldn't dissolve pain.

Student: You shouldn't?

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche: You should raise pain! Otherwise you won't know who you are and what you are. Meditation is a way of opening. In that particular process, under-hidden subconscious things come up, so you can view yourself as who you are. It is an unpeeling, unmasking process.

Student: How is that related to freedom?

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche: Because there is a sense not of collecting but of an undoing process. You don't collect further substances that bind you or further responsibilities. It is a freedom process."

Trungpa Rinpoche calls this tendency to reinterpret the teachings from our confused perspective "editing the teachings." We are interpreting the words and concepts of Dharma through the lens of dualistic fixation and then attempting to achieve the goals projected with this confused mind. This is a degenerative aspect of how people use the concepts of spirituality to reinforce habitual mind. You know..."Spiritual Materialism." It's the same corruption we find in approaches to the teachings which promise that you can use them to be a better business leader or improve your golf game. It is the same as using Buddhist concepts to address social issues like racism or sexism. It would be better to use Buddhist concepts to be better at mowing the lawn or washing the dishes. At least these tasks involve a certain directness.

When students are promoted into a teaching role too early, before they have been cooked in the environment of non reference point experience, they end up teaching confused dharma. This situation is rampant in America.

As practitioners we just explore this open wound, our dis-ease, our feeling of discomfort and groundlessness with no promise of an answer. What we find is this pain is actually the answer. We have been running from it since beginningless time-- isn't it time we stop and turn around to face it? As Trungpa would say-- "The question is the answer." This is what the Buddha did when he poked his head out of his palace and he saw the devastating reality of birth, old age, sickness and death. That created a gap in his discursive mind. It was terrifying to his notion of permanence. He also saw yogis practicing in the forest and he understood at that moment that rather than ignoring this reality the point is to go right at it.

If you have an authentic guru and lineage their actions and teachings will manifest non reference point experience. Once you recognize that in your guru then you know you are working with an authentic guru and lineage. That is the basis for your samaya. It doesn't matter at that point how your guru behaves from the conventional point of view.

Older students are so desperate to empower a younger generation that the training is watered down. The spiritual energy of the mandala of the guru and blessings in this profound lineage grows weaker and weaker.

People actually have no idea what non-reference point experience is.

"At this point I would like to shift our attitude from being big babies and discuss absolute symbolism. I hope you are up to it. Absolute symbolism is not a dream world at all, but realistic. As far as linguistics is concerned, absolute means “needing no reference point.” Otherwise, absolute would become relative, because it would have a relationship with something else. So absolute is free from reference point. It is wholesome, complete by itself, self-existing.

The idea of absolute symbolism is also passionless and egoless. How come? Actually, as far as absolute is concerned, you don’t come but you go. It is a going process rather than a coming process, not a collector’s mentality, in which you store everything in your big bank with fat money behind it, or your big bottle.

Absolute symbolism is egoless, because you have already abandoned your psychological reference point.

That doesn’t mean you have abandoned your parents, or your body, or anything of that nature. So what is that reference point? It is a sense of reassurance that makes you feel better. It’s like when you are crying and your friends come along and hold you and say, “Don’t cry, everything’s going to be okay. There’s nothing to worry about. We’ll take care of you. Take a sip of milk. Let’s take a walk in the woods, have a drink together.” That type of psychological reference point is based on the idea of relative truth.

The absolute truth of egolessness does not need any of those comforts. But that is actually a very dangerous thing to mention at this point. I have my reservations as to whether I should talk about these things, and since I have lost my boss, I have no one to talk to. So I decided to go ahead and tell you.

A sense of empty-heartedness takes place when we lose our reference point. If you do not have any reference point at all, you have nothing to work with, nothing to compare with, nothing to fight, nothing to try to subtract or add into your system at all.

You find yourself absolutely nowhere, just empty heart, big hole in your brain. Your nervous system doesn’t connect with anything and there’s no logic particularly, just empty heart.

That empty-heartedness could be regarded in some circles as an attack of the evil ones and in other circles as an experience of satori, or sudden enlightenment.

People actually have no idea what non-reference point experience is. When you begin to abandon all possibilities of any kind of reference point that would comfort you, tell you to do something, help you to see through everything make you a better and greater person—when you lose all those reference points, including your ambition, the strangest thing takes place. Usually people think that if you lose everything—your ambition, your self-centeredness, your integrity and dignities—you will become a vegetable, a jellyfish. But it’s not so. You don’t become a jellyfish.

Instead, you are suspended in space, in a big hole of some kind. It is quite titillating. Big hole of suspension! It’s as if you were suspended in outer space without a space suit or rocket ship. You are just floating and circulating around the planets forever and ever." Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

The Boundary

In "The Early Tantra Groups" Trungpa Rinpoche describes the practice of meditation as resolving natural awareness through what is percieved as the boundary. The "boundary" is the realization that we have been daydreaming. That perspective is already outside of the daydream. That momentary realization is called co-emergent wisdom and "self-liberation." We should understand every meditation method from this perspective. In the Mahamudra system one asks: "what color is the thought?" "Where does it arise; where does it dwell; where does it go?" As soon as you ask these questions you have stepped outside of the daydream of that thought fixation. When you understand the view in this way you understand every method of practice presented in the nine yanas.

"Absence of dualism is the synchronization of body and mind; and that is the result of fearlessness." Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin

"So we discover the Third Noble Truth, the truth of the goal: that is, nonstriving. We need only drop the effort to secure and solidify ourselves and the awakened state is present. But we soon realize that just "letting go" is only possible for short periods. We need some discipline to bring us to "letting be." We must walk a spiritual path. Ego must wear itself out like an old shoe, journeying from suffering to liberation."

Trungpa Rinpoche

When we practice with the view in this way there is a feeling that natural awareness comes at us rather than that we have to work at it. Rather than walking on the path, the path begins to walk on us. Daydreams are unsustainable. Reality always breaks through. Especially if we sit in a room where nothing is happening, doing nothing. This is the self-existing intelligence of rigpa that doesn't need the confirmation of habitual mind. We need to be fearless about this because we are attached to trying to solve the problem of our feeling of insecurity by spinning intensely in our minds--trying to fill a gap which cannot be filled. So this type of practice takes fearlessness. The fearlessness to sit in the midst of this panic attack of habitual mind and let be in that. This is the big secret. Sitting in a room where nothing is happening, doing nothing is terrifying for habitual mind. It is not psychologically comforting.

"Well, it is obviously a terrifying prospect that you cannot have ground to stuggle with, that all the ground is being taken away from you. The carpet is pulled out from under your feet. You are suspended in nowhere--which generally happens anyway, whether we acknowledge it as it actually happens or not. Once we begin to be involved with some understanding, or evolve ourselves toward understanding the meaning of life or of spirituality, we have no further reinforcement--nothing but just being captivated by the fact that something is not quite right, something is missing somewhere. You have to give in somewhere, somewhat-- unless you begin to physically maintain that particular religious trip by successive chantings pujas and ritual ceremonies. Or you may try to organize that spiritual scene administratively--answering telephones, writing letters, conducting tours of the community. Then you feel that you are doing something. Otherwise there is no ground to relate with, none whatsoever--if you are really dealing with the naked body as an individuality, an individual person who is getting into the practice of a spiritual way. Even with a person's obligations, administrative work, or liturgical job within the spiritual scene, he or she has nothing left on the spiritual way." Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

"Things as they are" is experienced by sems as suffering and insecurity because experience cannot be solidified by habitual mind. That is the Truth of the Four Noble Truths. We experience the reality of rigpa as suffering from the Hinayana perspective. Sems is the operation of habitual mind which is continually attempting to solidify what arises through projection and fixation. This is why we refer to the awareness outside of sems as "ordinary" or "natural awareness." It is the activity of sems which is "extra ordinary ". Natural awareness isn't dependant upon the activity of sems. In that way it is completely ordinary and "unborn."

Trungpa Rinpoche's Meditation Instruction

Formal meditation in our tradition is called "shamatha-vipashyana." This is the sanskrit term. In tibetan it is called "shine-lakthong." These two words correspond to the method and result of practice. Shamatha is the point of contact with "now" beyond habitual reference point. Vipashyana is then encountering whatever arises from the point of view of "nowness"--everything which arises has the texture or one taste of non reference point. That goes for what we think of as outer experience, inner thoughts and emotions and this cognizing awareness itself.

Shamatha is a momentary experience which cannot be maintained or fabricated. It is like the moment of yelling "PHAT!" Or the moment we trip over the coffee table on our way to the bathroom. Vipashyana is the experience of the echo of that point of contact. In reality shamatha and vipashyana are the same thing-- but as practitioners we describe them as two elements of the experience of practice.

Shamatha can be regarded as the "primordial dot." In practice that is the moment that we come back to the experience of the outbreath. Vipashyana is that "dot" spreading out to fill "the whole of experience." This is experienced as everything that arises -- thoughts, perceptions, etc. without any overlay of habitual hope and fear.

In the contemplative Japanese arts like Kyudo and Shado these two aspects are called "isshin" and "zanshin" which are translated as "the mind of oneness" and "left-over mind."

So how do we do that in our formal practice? The answer is, "We follow Trungpa Rinpoche's instructions."

"For just a moment we meditate on unobstructed, pure dharmata. This experience is vividly real but truly nonexistent, like waking from a dream. To the guru of gurus, uninterrupted consciousness without a reference point, I prostrate." Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin

The problem for most practitioners of sitting meditation is that they try to maintain a state of mental clarity and "not thinking" by watching their minds like a cat watches a mouse. Their practice becomes a rigid concentration practice which only reinforces habitual mind by repressing thought and maintaining a watcher. Trungpa Rinpoche joked that this was like trying to be a guest at your own funeral. In order to counter this tendency and yet still maintain a formal practice with the necessary discipline Rinpoche gave his students a practice which he called "touch and go."

Again, we sit in the formal meditation posture. Our eyes are open but not focusing on any one thing in the room or environment. Then we use the "outbreath" as the point of contact with nowness. As you breath out you have an overall sense of being present with the breath. You are here with the "outbreath." In the next moment you let go of that awareness of the breath. So on the inbreath you let go of the breath as the focus of your awareness. Then with the next outbreath you "be aware" of breathing out again. While we are doing this practice we notice that we are carried away by "thinking"-- full blown fantasies or very subtle thoughts. We notice this because at some point we remember to go out with the "outbreath" and, at that moment, we realize that we have been daydreaming. The instruction is to mentally label the daydream "thinking" and return to the momentary awareness of the outbreath. The point is not to attempt to remain in a state of "not thinking." The watcher is abandoned after the outbreath. Whatever thoughts arise don't matter at all to this technique. The main point is that there is a complete shift of perspective in the moment where you shift from engaging the daydream to being present with the outbreath. This is characterized as a leap. It is decisive and momentary. There are no lifelines or safety nets attached-- that is why it is beyond hope and fear.

This is very important to know in the moment of death.

"In one moment complete enlightenment."

The main point is that during your formal meditation session you notice again and again when you have been following a storyline or thought process. The moment you notice is Rigpa. Then let be for a moment. Relax. "Rerax."

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche calls this "resting in naturalness and sustaining freshness.".

Labeling the thought "thinking" accentuates that moment. Coming back to the direct experience of the breath is refreshing that natural awareness-- then rest there till that becomes diffused and distracted. Then do it again. Short moments many times.

"The pleasures and painful states you have in dreams are all of an equal nature the moment you wake up. Likewise, the states of thought and nonthought are of equal nature in the moment of awareness." Tsele Natsok Rangdrol "The Heart of the Matter"

Through continuing to practice in this way natural awareness infiltrates or erodes that experience of boundary--much as the ocean erodes and undermines the mainland. There is no attempt to create or maintain a still, peaceful or clear meditation state at all. That approach is ego's mimicry of meditation --which is all habitual mind can come up with. There will always be a watcher involved in that technique which is how habitual mind co-opts the practice.

Whether there are thoughts or stillness isn't the point-- the point is that we wear out the tendency to respond to what arises with habitual hope and fear-- we refer to this wearing out process as "shinjang." Shinjang is a tibetan word which Trungpa Rinpoche translated as "processed out." Delusion is processed out with awareness which is self-existing-- beyond hope and fear-- needing no dualistic reference point. "Vidyadhara's are worn out into realization," as the saying goes. In Dzogchen this is referred to as "the exhaustion of phenomena."

If there is an habitual reaction to what arises in the mind then that is daydreaming-- the five skandhas; the 12 nidanas; the five kleshas. If you simply recognize a thought as a thought while having the one taste of "nowness" or jinlap that is co-emergent wisdom or self-liberation. You are "free" of the thought not by rejecting it or repressing it with some concentration technique. You're free of the thought because marigpa-- coemergent ignorance-- has been infiltrated.

Essentially, meditation is fucking up dualistic mind and recognizing reality.

Realization , we could say is growing accustomed to that reality.

When you are confused there is the tendency to think of this as attainment or "credentials".

True realization means you are fucked-- totally fucked--mahasukkha-- great bliss. In the four yogas we talk about this as "one taste" and "nonmeditation."

"In terms of reality we are talking about everything which is percieved in the past, present or future. So that being the general description of samsara and nirvana we should go into that a little bit more and talk about shunyatha, because I think that is a key word and key phrase and a key doctrine of the Buddha. Shunyatha--shunya means "empty"-- and "tha" adding the "tha" to it means "emptiness." Or you could say "voidness", or "nothingness", but "emptiness" seems to be the best translation. "Empty" here means empty of all characteristics. All conceptions,; all predilictions; all predispositions. So emptiness has no characteristics, is not inclined toward anything and has no solid conception. And the "tha" or the "ness" quality invokes an active aspect to this "empty." That means that its not an emptiness that is simply a blank emptiness or numbness. Rather it means emptiness as what we could call a vivid clarity. The "ness" part means "vividness," and "clarity." The "empty" part is without any conditions.. So, let us say at this point that we could say that that is shunyatha..

Further, "ignorance" in sanskrit "avidya." A translation of that is "bewilderment." Ignorance, or bewilderment, results in the appearance of duality as samsara and nirvana. In other words, confusion and chaos and conceptuality. But this ignorance should not be regarded in the usual way that we talk about as stupidity. This ignorance is rather more like that sense of panic that one has in ordinary situations. When you are going along in a patterned fashion and suddenly (snaps finger) something interrupts that pattern there is a panic which is without foundation. And that panic leads to freezing of the ongoing quality of shunyatha or the continuity of shunyatha. So shunyatha becomes frozen and then becomes what is normally called in psychological terms "anxiety." Which is based on fundamental concept, and fundamental concept here is ignorance. In other words, when we begin to conceptualize, that conceptualization comes out of nothing. But begins to solidify as basic underlying fear or anxiety." Vajra Regent Osel Tendzin

The key point in our formal practice is not to try to repress "thinking." It is the moment that you realize you are distracted. That is meditation in this context. What comes next is "post-meditation" and ensuing cognition. The main point is the dividing line that occurs right there. You don't have to try to continue "thinking" and you don't have to try to continue "not thinking." That is the way we wear out or "purify" habitual reaction to what arises. In that way, the five skandhas become the five Buddha families and thoughts of the five kleshas are self-liberated.

"As we discussed in the chapters dealing with spiritual materialism, many people make the mistake of thinking that, since ego is the root of suffering, the goal of spirituality must be to conquer and destroy ego. They struggle to eliminate ego's heavy hand but as we discovered earlier, that struggle is merely another expression of ego. We go around and around trying to improve ourselves through struggle until we realize that the ambition to improve ourselves is itself the problem. Insights come only when there are gaps in our struggle, only when we stop trying to rid ourselves of thought, when we cease siding with pious, good thoughts against bad, impure thoughts, only when we allow ourselves simply to see the nature of thought." Trungpa Rinpoche

Jinlap

"The primordial dot spreads out to fill the whole of space." Trungpa Rinpoche

"The Tibetan word for adhistana is jinlap. Jin means "atmosphere," a particular type of atmosphere which is overwhelming. Somehow it has the connotation of producing a lot of heat. Its like entering a very clean room that is decorated with lots of gold, lots of brocade, and in which a certain very powerful person is living or presiding. When you go into that particular room you feel overwhelmed by the gold and brocade and everything, and you feel hot at the same time. There is that kind of potential melting quality, that you might actually get melted on the spot. So jin is that kind of atmosphere, that heavy sort of padma-ratna situation. And lap means "coming to you," that you are possessed by it. That is to say, you are receptive to that heavy atmosphere as well, and therefore you are engalloped by it, overwhelmed by it, sandwiched by it. So that is the meaning of jinlap, adhistana." Trungpa Rinpoche

"Not the domain of the ordinary person. Not known by someone of great learning. It is understood by the devoted, depends on the path of blessings, and is supported by the master's words." The Incomparable Gampopa

As a practitioner it is important to work within an authentic lineage. Until one truly resolves the nature of mind it is easy to go astray. The more one resolves the nature of mind through shamatha/vipashyana practice and the tantric path the more one comes to recognize it in one's authentic lama and lineage and their pith instructions. This realization dawns as an unmistakeable atmosphere or quality. This is what we generally refer to as adhistana or blessings. "Jinlap" is the Tibetan word for this. The experience of jinlap is the radiation of natural awareness. The center of this mandala is the lama -- they function as the pipeline for these blessings within the lama-mandala set-up. That is why the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages rely on Devotion.

"On the whole, if you want to become completely soaked in vajrayana discipline there is no other way than surrendering or giving in to the vajrayana master. There is no other way at all because without that, the whole magic and the whole system of openness could not occur at all. If there is none of that, then the rest of the situation becomes redundant." Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

"For the realization of Dzogchen to occur in your mind you must receive the transmission of the blessings of the mind of a master who possesses the lineage. This transmission depends on the disciple's devotion, so it is of sole importance."

And

"Devotion to the master is the king of all enhancement practices, so give up regarding him as an ordinary being. It is essential never to separate yourself from the devotion of seeing him as a Buddha in person."

Yogi Yanpa Lodi, the carefree vagrant

Maintaining a daily practice of 2 to 4 hours per day is essential. Without this we never accomplish the level of psychological awareness or subtlety necessary to distinguish between sems and rigpa moment to moment. And that is key. Beyond this one should engage in periodic intensive retreats and the full path presented by your lineage while living an ordinary life in whatever culture you live in. This is the path of the "hidden yogi."

Joining a monastery or living in meditation centers for extended periods of time only results in jaded dharma and spiritual materialism as the habitual mind develops a cozy world in these seemingly spiritual settings. So don't try to advance your "spiritual career" with these types of credentials.! Three to five years was the general rule for living at a Dharma Center under the direction of Trungpa Rinpoche. That seems like a good rule of thumb. The same is true for hanging out with the lama or the vajra sangha. The unique quality we are talking about in Dzogchen and Mahamudra is non reference point experience which is the radiation of natural awareness. If we try to make a cozy home in our spiritual career or relationship with the lama then our habitual mind simply co-opts the whole thing. This is the meaning behind the idea of not viewing the lama as an ordinary person. It has nothing to do with elevating some ordinary person within a superstitious patriarchal power structure so he can shower abuse on his students and take advantage of them. (This is how we generally view religious hierarchies in the West which obviously has a historical basis in Buddhist as well as so-called theistic traditions) It is very important to recognize the potential to misunderstand the purpose of this relationship and the mandala set-up. If we view it as an unequal power relationship, not only is that a mistaken view, but it will only ever lead to the abuse of that imaginary power. There is no way to utilize the skillful method of lama, mandala and devotion/mogu if we see the lama as someone who possesses primordial mind while we do not. Trungpa Rinpoche referred to this possibility as "idiot devotion." Turning the "vajra sangha" into a little friend group or "old boy" network is not such a good idea either. That isn't what they are for.

The Guru Principle

"The next section , which is connected with that awakening begins:

When the wild and wrathful father approaches

The external world is seen to be transparent and unreal

The reasoning mind no longer clings and grasps.

You are arriving in new territory. In spite of the depressions of theistic overhang or hangover, in spite of the theistic diseases that even Buddhists or other traditions can catch, you finally begin to realize that you don't have to dwell constantly on your pain. You begin to realize that you can go beyond that level, Finally you can celebrate that you are an individual human being. You have your own intelligence, and you can pull the rug from under your own feet, You don't need to ask somebody else to do that. You don't need to ask someone to pull up your socks-- or your pants, for that matter."

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Buddhism is a nontheistic tradition which means that the profound feeling you have in a teaching situation or practice mandala is primordial. It doesn't depend on being a good boy or good girl or on worshiping an external deity or the reincarnation of some great Tibetan master. It is based on a psychologically profound understanding of how we, as human beings, perceive jinlap or sacred world directly in our experience and work with that recognition as the basis of our nontheistic spiritual path. This is based upon something we call "devotion" in english. In Tibetan it is called "mogu." Mogu is a combination of feeling the wretchedness of samsara, of heartfelt longing and of sadness which is the essential aspect of the practice of guru yoga. "Devotion" is a very poor translation. The english language is not really suited to convey nontheistic spirituality. The history of english is rooted in theism. That is why it is so important to understand how Trungpa Rinpoche has translated these words -- what the real meaning is from the experiential path of practice. Therefore, generating mogu in one's practice is not the same as having a conceptual attitude or theistic belief system. It is not the same as being a loyal subject of the king of Shambhala. Having a belief that the guru is a superior being who you need to worship in order to receive their blessings is a fundamental misunderstanding of the view or spiritual purpose of a mandala set-up in the buddhist tantric tradition. Trungpa Rinpoche always cautioned against viewing the guru as a savior in this way.

"In guru-yoga, the practitioner begins to realize the nondual nature of devotion: there is no separation between the lineage and oneself and, in fact, the vajra being of the guru is a reflection of one's own innate nature. In this way, the practice of ngondro, culminating in guru-yoga, helps to overcome theistic notions about the teacher or about the vajrayana itself. One realizes that the lineage is not an entity outside of oneself: one is not worshipping the teacher or his ancestors as gods. Rather, one is connecting with vajra sanity, which is so powerful because of its nonexistence--its utter egolessness.

Trungpa Rinpoche

The tulku system as it exists today is based on the notion of the " blessed Tulku." It isn't based on nepotism or the metaphysical belief of a tulku as the literal reincarnation of a previous master. Although certainly there are instances of great masters who were reincarnated especially in Tibet and India in the old days, this type of tulku was rare then and is even more rare today. We don't think of Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa or Milarepa as this type of tulku, particularly. Today, if you are practicing within an authentic lineage and have received these blessings thoroughly-- you have become in a sense a blessed tulku as well. Therefore you can transmit this authentic dharma-- which is good news. That doesn't mean that we should dress in robes and give abhisekas. It is a lot simpler than that.

Through our practice and genuine realization we can create an auspicious situation for others. It really is the only hope for this authentic dharma free from the inherent corruption of "organized religion" and celebrity gurus to continue.

Coemergent Trigger Warning

To take a sip

of the choice intoxicant

while seated

on the dias

a slight smile

like a beautiful

tiger

his black hair

glistens

like healthy fur

I am not remembering this

It is a dream

I was not there

But now he is here

"We could do it with the fan: {opens fan}. First you see the fan --aaah! [displays the open fan]-- then you see the fan, second stage. The first kind of devotion comes like that. Its not so much bureaucracy and loyalty and territory particularly. But having started out with fear of the profundity, with being awe inspired, then you go aaah! [opens fan], and then you click after that. You have so much reverence for the vajra master who actually created that particular situation, the whole thing. That is what we already did a few minutes ago, and we are still doing it here--aaah! [opens fan]. We are doing it on the spot. Then loyalty begins to happen.

Loyalty means having a sense of oneness with that openness--aaah[opens fan]. You are loyal to that. So you find that as students you are beginning to share the mind of the teacher, the vajra master. You begin to catch glimpses of the vajra masters mind on the spot. Even in terms of memory or confirmation or whatever--aaah![opens fan]--you have it."

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

The center of the mandala is always ordinary mind-- natural awareness. Because we have practiced according to our guru's instructions we recognize it and go towards it. What you recognize in an authentic teacher is this same "ordinary mind." That is what we have faith in and what we long for and what the practice of devotion/mogu is based on. It's not based on a superficial hierarchy or some famous celebrity guru who has written lots of books who you have chosen from a mind of habitual reference point. You have to see it directly and that depends on your practice.

"You cannot have complete devotion without surrendering your heart. Otherwise the whole thing becomes a business deal. As long as you have any understanding of wakefulness, any understanding of the sitting practice of meditation, you always carry your vajra master with you all along. That is why we talk about the mahamudra level of all-pervasive awareness. With such awareness, everything that goes on is the vajra master. So if your vajra master is far away, there is really no reason for sadness-- although some sadness can be useful, because it brings you back from arrogance."

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Mandala Principle

This principle is beautifully illustrated during tantric feast practice in which the participants are all the vajra sangha of Trungpa Rinpoche. We all have our roles in the feast whether you are a chopon (shrine attendant) or dorje loppon (vajra master). When you have engaged properly in the practice of establishing a sacred mandala--i.e. have kept samaya and done your practice-- then one recognizes the nature of mind as the atmosphere of that situation. The dorje loppon is just a practitioner -- in this case, a member of the vajra sangha. He could have been your roommate when you lived in Boston. The role is on a rotating basis. You don't need to be the reincarnation of some great Tibetan Master to be the dorje loppon at a vajra feast-- but you certainly can manifest the primordial nature of mind within that mandala along with all the other participants in that sacred mandala. That is because the vajra sangha have all received authentic transmission from their lineage guru and they have the right kind of faith in nonreference point experience. In other words, they have learned how to pull the rug out from under their own feet. That blessing (jinlap) is manifest in the feast practice.

It is true that Trungpa Rinpoche was a great mahasiddha-- I have no doubt about that. He has been dead for close to 40 years at this point. People have the same doubts today when he is not here in person as they had when he was here. People think they need to find a living "guru" with the right credentials. Even sitting in the midst of the atmosphere of blessings so thick you could walk on it-- still people have doubts.

Is this it? Is this for real? Yes, it is real.

One needs to cut through doubt and hesitation with genuine practice-- flashing or leaping beyond dualistic fixation. The confirmation is obvious and needs no external reference point. The proof is in the pudding.

These profound blessings are manifest whenever we get a bunch of Trungpa Rinpoche's students together to engage his teachings and to practice according to his instructions. It doesn't matter if they are new or old students-- if they met him in person or not. We all meet the authentic transmission of the practice lineage in this way -- it is the same as meeting Padmasambhava face to face.